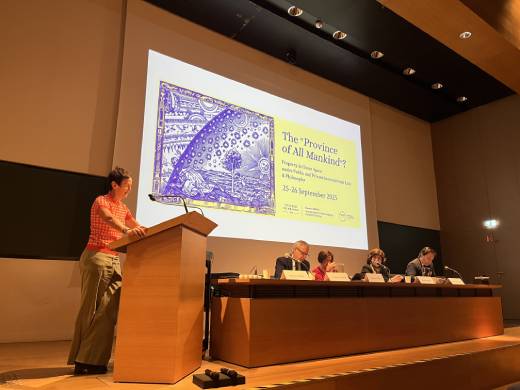

At the Collège de France, a symposium brought together lawyers and philosophers to discuss the issue of property in outer space. The symposium, entitled The Province of All Mankind: Property in Outer Space under Public and Private International Law & Philosophy, was led by Samantha Besson, professor of law at the Collège de France, as part of PEPR Origins, an interdisciplinary research program aimed at better understanding the origins of life, whose social sciences and humanities component is coordinated by the Collège de France.

A unique dialogue

Specialists in public and private international law compared their points of view and often disjointed legal traditions: property as understood by private law and as envisaged by publicists. Philosophers, for their part, questioned the very foundations of the concept of property: how can we talk about possession when it comes to a space that, by its very nature, transcends borders and should belong to humanity as a whole?

At the heart of the discussions was the interpretation of Article II of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which enshrines the principle of non-appropriation, and its articulation with Article 11 of the 1979 Moon Agreement, according to which the Moon and celestial bodies constitute the common heritage of mankind.

These two provisions were weighed against initiatives that partially challenge them: namely, the Artemis Accords, or national space laws that provide for property rights over space resources (Luxembourg, United States, Japan, etc.). Samantha Besson outlined this tense legal landscape in her introduction to the symposium.

Beyond the question of ownership itself, discussions, particularly those led by Stefan Hobe (University of Cologne) and Anna Stilz (University of Berkeley), focused on its links with sovereignty, as well as on issues of state competence and jurisdiction over space resources.

Between scientific exploration and commercial exploitation

The discussions highlighted the tension that can exist between scientific research and commercial exploitation of space resources. The Moon, for example, is caught between scientific programs seeking to better understand its surface and others that boast of prospecting resources for future use. The contributions explored this tension, drawing on legal analysis, philosophy, and sometimes international relations.

Among the contributions, Fabio Tronchetti from Northumbria University invited participants to redefine the concept of common heritage in light of lunar mining projects. Michela Massimi (University of Edinburgh) drew a parallel between the management of space resources and that of the seabed, noting that both international spaces are subject to similar tensions. Jonathan Wiener (Duke University) examined the political and environmental implications of space as a province, property, or protection issue.

Collective responsibility

Stéphanie Ruphy, Scientific Director of the ENS-PSL Space Chair, emphasized the need to maintain a clear distinction between scientific research and industrial logic in order to ensure that space activities benefit all of humanity.

She reiterated the need for vigilance in the face of attempts to appropriate celestial bodies, whether private or national, and emphasized the collective responsibility that any space venture entails.

In the context of the race for mineral resources on the Moon, speakers outlined the idea that it is still possible to extract Earth’s natural satellite and celestial bodies from the colonial and extractivist logic that has marked history, but that this requires sufficiently binding mechanisms of international law.

The last afternoon of the conference was devoted to a general discussion among young doctoral students, including two of our associate researchers, Katia Coutant and Alban Guyomarc’h, who gave their perspectives on the exchanges and proposed avenues for reflection based on their respective research.

Photo credit : Alban Guyomarc’h